The United States is grappling with an unprecedented labor shortage in blue-collar and manufacturing roles, creating a structural challenge for the economy. Job openings in industries from manufacturing to construction far outnumber available workers. As of late 2021, U.S. employers had about 10.9 million vacant positions – roughly 1.7 open jobs for every unemployed worker . The Conference Board warns that these labor shortages – especially in blue-collar jobs – will likely continue through at least 2030, risking declines in the nation’s productivity and living standards if left unaddressed . This article examines the root causes of the labor shortfall, reviews key data trends of the past decade, projects the outlook for the next 10 years, and discusses how industry leaders and new technologies (including robotics and “embodied intelligence” ) are working to solve this crisis. We also include expert commentary – from veteran economists to voices like Elon Musk – on what the future may hold.

Causes of the U.S. Labor Shortage

Causes of the U.S. Labor Shortage

Several structural factors have converged to create the current labor shortage in blue-collar and manufacturing sectors: • Declining Interest in Blue-Collar Careers: Cultural and educational shifts over recent decades have reduced domestic interest in manual trade jobs. A growing emphasis on four-year college degrees has led fewer young people into vocational training or apprenticeships . Traditional pipelines for skilled trades have weakened, and younger generations are showing less interest in pursuing careers in industries like manufacturing and construction . Societal biases also play a role – for years, white-collar professions have been seen as more prestigious, deterring many youth from considering well-paying skilled trades despite the competitive wages and advancement opportunities these jobs offer . This cultural shift means the pool of candidates willing to do blue-collar work has shrunk, even as demand for these roles grows. In fact, as Americans attain higher education in greater numbers, the share of the workforce without a college degree (those who typically fill blue-collar jobs) has been steadily shrinking and is projected to shrink even faster in the coming decade . • Aging Population and Declining Birth Rates: Demographics are a major driver. The Baby Boomer generation, which supplied a large portion of America’s blue-collar labor, is retiring in droves. Nearly one-third of manufacturing workers are now over the age of 55 , and their retirements accelerate each year. As these experienced workers exit the workforce, industries lose not only headcount but also decades of institutional knowledge “walking out the door” . Meanwhile, younger cohorts are smaller in size. U.S. birth rates have trended downward since the Great Recession, hitting a historic low in 2020 and showing little sign of recovery . This persistently low fertility rate means fewer entrants to the future workforce, causing the population to age at an accelerated rate . By 2030, all Baby Boomers will be at or past retirement age, and the U.S. will, for the first time, have more seniors than children. The result is a double strain: a swelling retiree population and a diminishing working-age population. Indeed, since 2020 the number of U.S.-born people aged 18–65 has begun to shrink rather than grow . This demographic shift is unprecedented – the U.S. has never before seen a wave of retirements alongside near-zero growth in its working-age population . It’s a primary reason labor supply is tightening across blue-collar industries. • Restrictive Immigration Trends: Immigration has historically helped fill gaps in the U.S. labor force, especially in physically demanding or lower-wage jobs that struggle to attract domestic workers. In recent years, however, immigration flows have slowed markedly due to policy changes and other factors. Net international migration added only about 247,000 people to the U.S. population between 2020 and 2021, a 76% drop compared to the mid-2010s (when over 1 million people were added in 2015–2016) . This means far fewer foreign-born workers are entering the labor pool. Notably, immigration policies since the mid-2010s became more restrictive, especially for workers without advanced degrees. Current policies largely do not allow many non-college-educated immigrants to enter and fill blue-collar jobs, even where demand exists . According to an analysis by economists Giovanni Peri and Alessandro Caiumi, the net inflow of less-educated immigrants – who traditionally take roles in sectors like agriculture, construction, hospitality, and manufacturing – turned negative in the late 2010s . In other words, more lower-skilled workers have been leaving or aging out than new ones arriving. This pullback, combined with pandemic disruptions, has created labor shortages in occupations that historically relied on immigrant labor (from farm workers to meatpackers). Immigration had been a “countervailing force” slowing the workforce decline, but with that valve tightened, the U.S. must now contend with labor scarcity largely on its own .

In summary, fewer Americans are pursuing blue-collar careers, a large generation of workers is retiring, the domestic birth rate is low, and immigration – once a pressure release for tight labor markets – has been curtailed. All these factors shrink the supply of available labor, even as demand for workers in manufacturing, construction, logistics, and other manual fields has surged with a growing economy.

A Decade of Declining Labor Supply: Trends in the 2010s and 2020s

A Decade of Declining Labor Supply: Trends in the 2010s and 2020s

These structural forces have been building for at least a decade, and the data bear this out. Over the past 10 years, the U.S. labor force participation rate and growth of the workforce have trended downward, particularly among groups relevant to blue-collar employment. After steady expansion in the late 20th century, labor force growth has slowed to about 0.66% annually from 2004 to 2024, a sharp drop from the ~2% annual growth rates seen in the 1960s–1980s . In fact, U.S. workforce growth has essentially flatlined in recent years, roughly mirroring the country’s slow population growth . This deceleration means that each year the labor pool adds fewer new workers than in past generations.

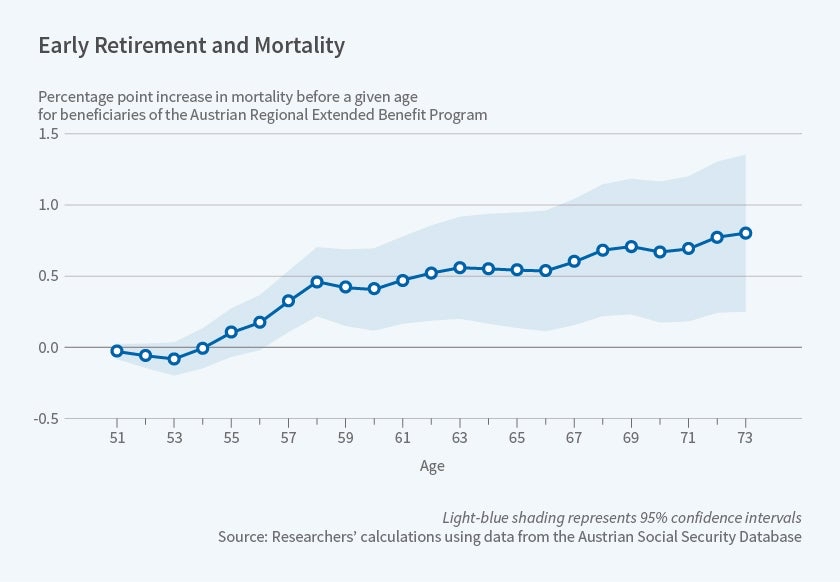

Under the surface of aggregate figures, the composition of the labor force has shifted in ways that highlight the blue-collar pinch. The number of Americans without a college degree has been decreasing every year since 2010 . Crucially, this non-college-educated group – the core of many blue-collar talent pools – shrank by over 800,000 people per year in the late 2010s , due to smaller youth cohorts and more young people pursuing higher education. In parallel, the U.S. saw a surge in retirements in the late 2010s and early 2020s. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this trend: out of 5 million people who left the labor force in 2020, a disproportionate share were over 55, and many of those older workers have not returned . It took about two years for the labor supply to rebound to pre-pandemic levels, and even then a persistent gap remained due to early retirements by older workers . Today, labor force participation among seniors (65+ or even 55+) remains well below pre-2020 levels, effectively removing millions of would-be workers from the economy .

Labor force participation for prime-age workers (25–54) has recovered near historic highs by 2025, yet the overall participation rate is weighed down by the drop-off in older and young workers . The reality is that labor force participation is unlikely to ever fully return to past highs, given these demographic headwinds. Government projections estimate the overall labor force participation rate will fall to 60.4% by 2030, nearly three percentage points lower than it was in early 2020 . In short, a smaller share of Americans will be working or seeking work going forward, primarily because the population is aging and growing more slowly.

Importantly, these trends have been especially acute in manual and industrial sectors. Industries like manufacturing and trucking, for instance, entered the 2020s with aging workforces and difficulty attracting young talent. Over the past decade, manufacturing employment had stabilized after decades of decline, but by late 2010s many factory operators reported a critical skills gap – not enough qualified welders, machinists, technicians, and production workers to replace retiring employees. Open positions piled up. By 2018, economists noted that labor markets for blue-collar workers were significantly tighter than for white-collar workers, reflecting robust demand but a shrinking supply of interested workers . Sectors like construction, warehousing, and transportation likewise saw chronically high job vacancy rates through the late 2010s, even before the pandemic. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce reported that many industries simply could not find enough workers to fill open jobs, and if every unemployed person in the country were hired, there would still be positions left unfilled . This was a stark change from historical norms and signaled a structural shortage, not just a temporary mismatch.

Future Projections: Labor Supply vs. Demand in the Next 10 Years

Looking ahead, the imbalance between labor demand and supply in blue-collar fields is expected to persist – and potentially worsen – over the coming decade. As of 2025, the total U.S. labor force stands around 168 million people . By 2030, that number will grow only marginally (to roughly 170 million) under current trajectories . Yet the needs of key industries are growing much faster. Manufacturing, for example, faces an enormous labor shortfall if current trends hold. A study by The Manufacturing Institute and Deloitte projects that U.S. manufacturers will need to fill about 4 million jobs this decade, but 2.1 million of those positions could go unfilled by 2030 due to a lack of skilled workers . This gap amounts to lost production and opportunities – Deloitte estimates that failing to fill those jobs could cost the U.S. economy $1 trillion in 2030 alone .

Other projections are similarly eye-opening. The construction sector, amid an infrastructure boom, continues to report widespread worker shortages – for instance, 91% of construction firms are struggling to find qualified workers to meet demand . In the semiconductor industry, which is expanding domestic chip manufacturing, companies plan to add around 115,000 jobs by 2030 – but based on current engineering graduation rates, as much as 58% of those positions could remain unfilled . The Semiconductor Industry Association warns that without enough skilled technicians and engineers, efforts to reshore chip production will be hampered, noting “if we aren’t able to get our arms around this, our industry…will falter” . Likewise, homebuilders foresee severe shortages of tradespeople (carpenters, electricians, plumbers) over the next decade, which could bottleneck housing and infrastructure projects .

These forecasts underscore a stark reality: labor demand in many blue-collar and industrial occupations will outpace the available supply of workers for years to come. By the mid-2020s, the U.S. had roughly twice as many job openings as unemployed persons in the labor force , and while economic cycles will ebb and flow, the structural shortfall in trades and manufacturing is largely baked in by demographics. Even if economic growth slows, critical sectors may still find it difficult to hire enough staff. The labor force is simply not growing fast enough to replace retiring workers or to staff ambitious national initiatives (from rebuilding infrastructure to revitalizing manufacturing) . In fact, The Conference Board estimates the U.S. would need to add 4.6 million workers per year – about four times the recent annual growth rate – just to keep labor supply and demand in balance . Barring an unforeseen baby boom or a radical change in immigration policy, such explosive labor force growth is highly unlikely. This means companies and policymakers must prepare for a world where workers are a constrained resource.

Challenges to Revitalizing American Manufacturing

The labor shortage poses a serious challenge to U.S. efforts to reshore and expand domestic manufacturing. After decades of offshoring, there is strong momentum (and government support via initiatives like the CHIPS Act) to build more factories in America – whether for semiconductors, batteries, electric vehicles, or pharmaceuticals. However, revitalizing manufacturing is not as simple as building facilities; those facilities need skilled hands to run them. Companies are already encountering this reality. For example, Taiwan’s TSMC, the world’s largest contract chipmaker, is investing $40 billion to open advanced chip fabs in Arizona – but progress has been slowed by a shortage of skilled construction and installation workers. TSMC’s chairman bluntly stated in 2023 that “there is an insufficient amount of skilled workers” with the expertise to build a semiconductor factory, forcing the company to delay production start dates and even consider flying in hundreds of experienced technicians from Taiwan to train the local workforce . This instance illustrates a broader point: even when capital and political will are available to grow U.S. industry, the lack of a ready workforce can become a bottleneck.

Manufacturing firms nationwide echo similar concerns. In surveys, 77% of manufacturing executives say the labor shortage is their biggest business challenge . Unfilled jobs mean production delays, which in turn threaten contracts and expansion plans. Companies must often pay overtime or hire less-experienced workers to keep assembly lines running, raising costs and sometimes compromising quality . In heavy industries and aerospace, veteran craftsmen are retiring faster than new ones are trained, leading to knowledge gaps on factory floors. The National Association of Manufacturers has cautioned that without a pipeline of skilled workers, the sector’s growth and innovation are at risk . In short, the labor shortage could undermine the very gains that manufacturing revival programs aim to achieve. As The Conference Board observed, without concerted action, labor scarcity in blue-collar fields will make businesses less competitive and act as a drag on economic growth . Ambitious infrastructure upgrades, energy projects, and industrial expansions could be hamstrung by lack of manpower. This challenge puts the onus on both public and private sectors to find solutions – whether through better training, productivity improvements, or new technologies – that enable growth despite a tighter labor market.

A Founder’s Mission in Workforce Solutions

Tackling a challenge of this magnitude requires vision and long-term commitment, and that is exactly what some leaders in the field of workforce solutions have embraced. One notable example is the mission driven by our founder – a visionary who recognized these labor force trends early on and has dedicated his career to addressing them. For years, the founder has been sounding the alarm on the structural mismatches in the U.S. workforce and pioneering strategies to bridge the gap. This mission has spanned from improving job training and placement programs to advocating for policy changes that remove barriers to work. For instance, under his leadership, our organization has invested in modern apprenticeship models to funnel more young people into trades, created upskilling initiatives to help workers transition into in-demand industrial roles, and advised companies on how to redesign jobs to be more attractive and accessible to American workers. These efforts directly target the root causes of the shortage: encouraging more domestic talent to enter blue-collar fields, transferring knowledge from retiring veterans to newcomers, and better aligning education with industry needs.

The founder’s long-standing philosophy is that workforce challenges can be solved by “meeting people where they are” – whether that means bringing training opportunities to underserved communities or designing technology that makes jobs easier and more productive. This outlook anticipated many of the issues grabbing headlines today. A decade ago, when labor market commentators were largely focused on offshoring and automation displacing workers, our founder was focused on the opposite problem: not enough workers for the jobs that needed to be done. He championed the idea that investing in human capital and augmenting it with smart technology would be key to sustaining industries. Now, as the labor crunch intensifies, that mission is more critical than ever. Our founder’s workforce solutions directly address the structural challenges we’ve discussed – from demographic shifts to skills mismatches – by creating pathways for people to enter and thrive in the trades and by deploying innovations that amplify the impact of each worker. In essence, the mission has been to ensure that businesses have the talent they need to grow, and that workers have the skills and support they need to seize these plentiful opportunities. It’s a win-win approach that speaks to investors (who worry about operational risks from labor shortages) and to policymakers (who seek inclusive economic growth).

Robotics and Embodied Intelligence: A Long-Term Solution

In addition to human-centered strategies, a critical piece of the long-term solution to labor shortages lies in technology – particularly robotics and “embodied intelligence” (具身智能). Embodied intelligence refers to AI systems integrated into physical machines (robots) that can perform tasks in the real world. As the supply of human workers tightens, automation offers a way to boost productivity and fill roles that can’t find sufficient manpower. We are already seeing this trend: in 2021, amid severe labor shortages, North American companies ordered a record number of industrial robots – nearly 40,000 robots (worth $2 billion) were purchased in that year alone, an all-time high, as firms sought to maintain output with fewer workers available . Automation, once driven mainly by cost-cutting, is now increasingly driven by necessity. Joe Campbell, a senior manager at a leading collaborative-robot maker, noted that “the number one driver for automation is the labor shortage in manufacturing”, highlighting that about 2,000 Baby Boomers retire from manufacturing jobs every day, leaving factories shorthanded . In other words, robots are helping to fill a void left by retiring humans.

The role of robotics is especially crucial in sectors like logistics, manufacturing, and even construction. Modern collaborative robots (“cobots”) can work alongside humans on assembly lines, handling repetitive or strenuous tasks and boosting overall productivity. This allows the existing workforce to be more effective – for example, a warehouse with automated picking robots can fulfill orders with far fewer staff, or a construction team can use robotic assistants for heavy lifting or precise installation work. Companies deploying such technologies report significant gains: some warehouses have doubled productivity with only half the usual staff by using robots to do the heavy lifting . Importantly, automation can take over not just manual labor but also roles where labor simply isn’t available. In sectors with chronic shortages (like long-haul trucking or food processing), autonomous vehicles and robotic equipment are being fast-tracked to fill the gap. Robotics thus serves as a force multiplier for a constrained workforce.

The role of robotics is especially crucial in sectors like logistics, manufacturing, and even construction. Modern collaborative robots (“cobots”) can work alongside humans on assembly lines, handling repetitive or strenuous tasks and boosting overall productivity. This allows the existing workforce to be more effective – for example, a warehouse with automated picking robots can fulfill orders with far fewer staff, or a construction team can use robotic assistants for heavy lifting or precise installation work. Companies deploying such technologies report significant gains: some warehouses have doubled productivity with only half the usual staff by using robots to do the heavy lifting . Importantly, automation can take over not just manual labor but also roles where labor simply isn’t available. In sectors with chronic shortages (like long-haul trucking or food processing), autonomous vehicles and robotic equipment are being fast-tracked to fill the gap. Robotics thus serves as a force multiplier for a constrained workforce.

Embodied intelligence also means these machines are getting smarter and more versatile. Advanced AI allows robots to adapt to complex, unstructured environments – a necessity for broader adoption in fields like caregiving, construction, or agriculture. For example, robotics firms are developing humanoid robots capable of basic facilities maintenance or material handling. Elon Musk has famously pushed the concept of a general-purpose humanoid robot: in 2022 Tesla announced “Optimus,” a humanoid robot prototype, explicitly intended to handle routine factory tasks. Musk stated that such robots could eventually address labor shortages in industries like manufacturing . While still in early development, the vision signals how critical robotics is viewed as a solution to labor scarcity. In fact, the integration of AI and robotics – true embodied intelligence – is seen as a key long-term answer to offset an aging, shrinking human workforce. Robots do not replace the need for human workers entirely, but they augment it: taking on jobs that are dangerous, undesirable, or simply unfillable, while humans focus on higher-level tasks and supervision. Over time, as technology improves, embodied AI systems will likely become as commonplace in factories and warehouses as computers are in offices.

Of course, adopting robotics at scale brings its own challenges (investment costs, worker training, etc.), and not every labor shortage can be solved by a robot. Careful implementation is needed to ensure automation complements the workforce and that displaced workers (if any) are retrained for higher-skilled roles. Nonetheless, for an investor or business audience, the message is clear: companies at the forefront of automation are better positioned to navigate persistent labor shortages, and the robotics sector itself is poised for growth as demand for labor-saving solutions rises. In the long run, embodied intelligence in machines may become one of the pillars that sustains economic growth in the face of unfavorable demographics.

Expert Perspectives on the Road Ahead

Leaders in technology and economics are increasingly vocal about the implications of this labor shortage and the role of automation. Elon Musk, for one, has frequently highlighted demographic decline as a critical issue. Musk warns that “population collapse is potentially the greatest risk to the future of civilization” – a bold statement underlining how a falling birth rate and aging society could undermine economic vitality. He points out that if people don’t have more children, “civilization is going to crumble, mark my words,” tying the labor force directly to the fate of the economy. Musk’s solution, in part, has been to invest in automation (like the aforementioned Optimus robot) to ensure productivity can continue even with fewer people. His view is that we must “solve the labor problem” through innovation, because simply relying on population growth is not feasible in the near term.

Economists and policymakers likewise acknowledge that the labor shortage is not a transient blip but a new reality to confront. Jerome Powell, Chair of the Federal Reserve, noted that labor force growth has fundamentally slowed, and has called for measures such as immigration reform to bolster the workforce. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and business groups are lobbying for policies to alleviate worker shortages – for example, by expanding legal immigration pathways and incentivizing work participation. Labor economists like MIT’s David Autor have discussed the need to improve job quality in blue-collar fields to attract workers, suggesting that higher wages (already rising in many trades) and better working conditions will be part of the solution . There is also a growing chorus advocating for more investment in career and technical education. As one recent Conference Board study recommended, promoting apprenticeships and vocational training, and changing perceptions about the trades, are vital to replenishing the blue-collar talent pipeline .

On the technology side, executives in the automation industry emphasize that machines are ready to do more. “Bring on the cobots,” says Joe Campbell of Universal Robots – he sees no slowdown in automation adoption on the horizon. The Association for Advancing Automation reported that 2021 was the strongest year on record for North American robot sales, and 2022 was on pace to set another record. This trend is often described not as replacing people, but as filling a void: robots are backfilling roles that companies simply cannot hire for. In the words of one industry CEO, “We’re automating because we can’t find the people. It’s as simple as that.” Analysts predict that sectors facing the toughest labor constraints – from manufacturing to healthcare – will be among the fastest adopters of AI and robotics in the coming years. Even policymakers view automation as part of the toolkit; for example, Japan and some European countries with aging populations explicitly promote robotics to care for the elderly or staff factories, setting a precedent the U.S. may follow.

Perhaps the most telling expert insight is a broad consensus that there is no single quick fix. The labor shortage requires a multifaceted response: immigration reform to boost the workforce in the short term, education and training reforms for the medium term, and technological innovation for the long term . Elon Musk encapsulated one aspect when he quipped that he’s “doing his best to help the underpopulation crisis” – a tongue-in-cheek reference to his own large family – but jokes aside, the crisis is real. As Musk and others acknowledge, if we don’t embrace solutions (from having more children to deploying more robots), the math doesn’t work out. In 20 years, there may simply not be enough working-age people to sustain the economy as we know it. That prospect has sharpened the minds of investors and executives alike, who now see workforce strategy as a key component of business strategy.

Conclusion

For media and investors, the U.S. blue-collar labor shortage is a story with high stakes. It’s about more than just today’s difficulty in hiring truck drivers or machinists – it is a fundamental realignment of the labor market that will shape the nation’s economic trajectory for decades. The causes are deep-rooted: cultural preferences, demographics, and policy choices have all played a part in constricting the labor supply. The data from the past ten years reveal a concerning trajectory, and forecasts for the next ten warn of even greater imbalances if nothing changes. Yet, this challenge is also spurring innovation and action. Companies are adapting by raising wages, improving working conditions, and investing in their workforce. Visionary founders and industry leaders are developing workforce solutions and championing the value of skilled trades. At the same time, robotics and AI are emerging as powerful allies, ensuring that productivity can continue even as human labor becomes scarcer.

For investors, sectors that provide automation, training, or other solutions to the labor crunch may represent significant opportunities in the coming years. For policymakers, supporting immigration, education, and technology development will be key to easing the strain. And for society at large, a shift in how we view blue-collar careers – recognizing their importance and dignity – will help draw more people into these essential roles.

In the end, the labor shortage is a complex problem, but not an insurmountable one. America’s economy has a long history of adapting to workforce challenges, whether through innovation or reinvention. This time will be no different. By addressing the root causes and embracing new solutions like embodied intelligence, the U.S. can turn a labor crisis into an opportunity – one that modernizes its industries, empowers its workers, and secures its future growth. As experts remind us, the time to act is now: the trends are in motion, and the next 10 years will determine whether we mitigate the labor shortage or simply live with it. The choices made today – by business leaders, investors, and policymakers – will write the next chapter in the story of the American workforce.

Sources:

- U.S. Chamber of Commerce – Understanding America’s Labor Shortage

- The Conference Board – Blue-Collar Labor Shortages Through 2030

- Conference Board (Giattino & Swift) – Why Blue-Collar Labor Markets Are Tighter

- Econofact (Peri & Caiumi) – Immigration and Waning Labor Force Growth

- Quickbase Blog – Skilled Labor Shortage in Manufacturing & Construction

- Manufacturing Institute/Deloitte – Creating Pathways for Tomorrow’s Workforce (2021)

- Reuters – Record Robot Orders Amid Labor Shortage

- Reuters – Elon Musk on Humanoid Robots and Labor Shortages

- Fox Business – Elon Musk on Population Collapse

- Fortune – TSMC Delays Arizona Fab, Cites Labor Shortage

- Bloomberg/SIA – Chip Industry Talent Shortage Projection

- The Conference Board – Responding to U.S. Labor Shortages (2024)